Today marks Veteran’s Day here in the United States. It’s a day we set aside to honor those who have fought so valiantly for our country.

With the advent of technology, reaching out to Veterans to declare your support is easier than ever before. Businesses, organizations, individuals – everyone is sending a shout out to Vets today. It is amazing to see the support flowing forth.

But.

I think there is an aspect we often forget about as we reach out to give our thanks to the vets who have fought for us through service in various branches of our military.

It is important to remember they are human too. They have emotions, reactions, and they too, are remembering their journey in their own way as we lavish them with praise and appreciation.

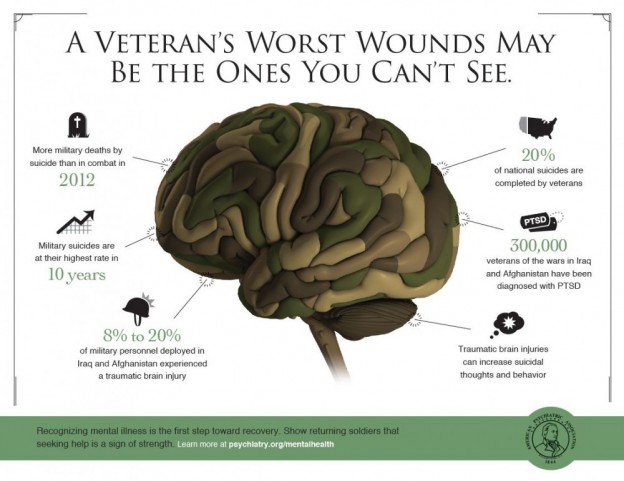

Some may struggle with PTSD. Others are lost in thoughts of brothers in arms lost to battle. Others contend with the idea that those who thank them for all they have taught them are themselves the teachers and worthy of praise.

We forget, all too often, I think, the intense emotional aspect of war. The toll it takes on all of us. Perhaps this is because best summed up by this quote:

“Humankind cannot bear very much reality.”

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

Is war something we are unable to closely associate with human emotion because of the very nature of it? Is battle too fierce? The fighting too gruesome? Do our psyches not allow us to carry the traumatic alongside the sensitivity? Is this our brain’s way of protecting us from an emotional overload? Or is it because the majority of soldiers for so long have been men and therefore not allowed to operate as anything less than robotic, keeping them from processing the emotions battle swells within them?

We do not broadcast our losses on the evening news as often as we should, a point made in this deeply moving post about a citizen sharing a last flight home by a soldier. Instead, we relegate ourselves to separation from the tremendous loss and focus instead on the reunions of soldiers with loved ones. We are not acknowledging, in my humble opinion, the steep and tragic cost associated with prolonged battle. The loss, the heartache, the raw emotions steeped in battle and drenched in blood shed against tyrants who dare to threaten our freedoms, are far too great for humanity to bear.

We, for whatever reason, do not often equate humanity with soldiering. Empathy and compassion fails to mesh well with the ferocity of battle. So when soldiering and emotion intersects, as it often does on Veteran’s Day for so many, it can be triggering. It may leave some feeling overwhelmed and not knowing quite how to deal with the gratitude flowing their way.

It is not like Christmas or Thanksgiving. We are not celebrating, we are honoring. There are no gifts or celebratory meals. Instead, there is quiet recognition and thoughtful consideration of all that our veterans have sacrificed. Like anything else, we all choose to do this differently for it is intensely personal for those of us who have a veteran in our lives. Whether they be friends, brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, grandfathers, or grandmothers, how we choose to honor their service and their memories is as unique as a snowflake which falls with the first snow.

We may choose to honor them quietly or we may make a public statement. For me, today, I am wearing my grandfather’s tag and will probably at some point watch Mister Roberts, a movie I used to watch with my grandfather quite often. Both of my grandfathers served in the Navy in WWII and although they never spoke of it with me, I knew they carried their experiences with them, as all veterans do. Military service is a part of their souls and the very fiber of their beings. Once you have served, there is rarely a time when you can untangle soldier from human. Therein, in my opinion, lies the challenge in coming to grips with the flow of gratitude on Veteran’s Day.

I only saw my grandfather cry once – when we were at a play meant to raise funds for the WWII D-Day Monument. As the telegraph notifications came in reporting the deaths of the soldiers in Bedford, Virginia, the hall went completely silent. Deeper than an audible silence; the kind of silence which envelops a room when there is great respect for what is occurring. I glanced over at my grandfather at this point to see his cheeks soaked in tears. I quickly looked away and struggled to hide my own flooded cheeks shortly thereafter. We never spoke of these tears but I never forgot them for they symbolized the emotional depths of war for me and always will.

For many, in particular those who have seen war since 2001, today is different. The memories are recent, the pain is ongoing, and they have joined the Greatest Generation in knowing the pain of war. Yes, the pain. War is not some glorified wonderful thing. It is not the Hollywood version where there is a rise to action, action, and then a conclusion. It’s messy, it rips families apart, it pushes soldiers to their limits and back again, and if they’re lucky, they get to come home, alive and still intact both physically and mentally. For all too many, this is not the case, and their wounds may not be visible to the eye.

Suicide rates among soldiers, for the first time ever, outnumbers the deaths occurring in active combat. There is PTSD, and number of additional other issues which, again, because of technology and advancements in mental health awareness & medicine, are now at the forefront of the adverse affects of war. Women who are deployed face a higher risk of Postpartum Depression which in turn, affects an entire generation. War truly leaves a mark on every one of us, both on and off the battlefield.

Suicide rates among soldiers, for the first time ever, outnumbers the deaths occurring in active combat. There is PTSD, and number of additional other issues which, again, because of technology and advancements in mental health awareness & medicine, are now at the forefront of the adverse affects of war. Women who are deployed face a higher risk of Postpartum Depression which in turn, affects an entire generation. War truly leaves a mark on every one of us, both on and off the battlefield.

So today, when you thank a veteran, particularly a younger veteran, take the time to embrace that they may be filled with emotions they may not be ready for today as a result of the onslaught of gratitude. Take the time to realize that these brave men and women have lost loved ones, brothers in arms, and they are replaying this in their heads as you thank them for their service. Respect their journey but also take the time to check in with them and ask them how they are doing.

For they are soldiers, they are brave men and women, but beneath it all, they have a heart, a soul, and they have bled for us, some more than others. They deserve nothing less than our greatest compassion and understanding for the hell they witnessed on the battlefield as they fought for freedom from tyranny in our great country’s name.